People Staring at a Great Ancient City Clip Art

Once you've been to Petra, information technology stays with y'all. Long later you've left you will find grit from Petra'due south red sandstone in the tread of your shoes; your fingernails will have a faint rosy tinge; a fine pinkish dust will cling to your clothing. For some fourth dimension you will close your eyes and still be able to relive the startling moment you start saw this ancient stone city rising out of the desert flooring; you will bask the memory of this place, its grandeur and strangeness, even afterward you manage to wash abroad the traces of its ruddy rocks.

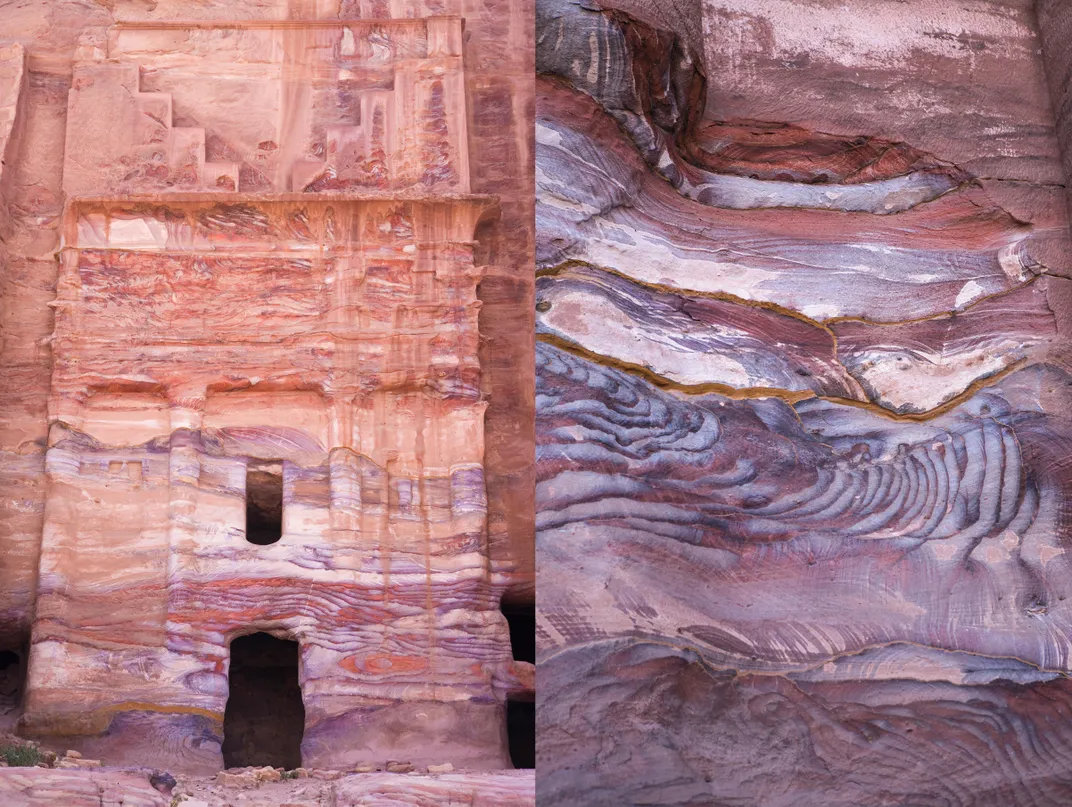

Driving southwest beyond the irksome plateau from Amman for a few hours, you all of a sudden tip into the dry bowl of Jordan's Arabah Valley and tumble down through mount passes. The landscape is cracked and sandy, seared and unpromising. It is hardly the setting in which you expect to observe a metropolis of any sort, permit alone one this rich and extravagant and refined. There seems to be no water, no possibility of agronomics, no ways of livelihood or sustenance. The fact that the Nabatean people, the nomadic Arabs who crisscrossed the region until they grew wealthy from trade, made Petra the capital letter of their empire by the fourth century B.C. is inexplainable. Withal here, at the valley'southward center, are the remains of this once-lavish city, watered by hidden aqueducts that run for miles from an underground leap. Information technology looks like no other identify I've ever seen. The "buildings" are punched into the rock cliffs—in other words, they are elaborate caves, recessed in the sandstone and fronted with miraculously carved ornate facades. Information technology is probably i of the world'south only cities that was made past subtraction rather than addition, a metropolis you literally enter into, penetrate, rather than arroyo.

Petra will describe you in, only at the same time, it is e'er threatening to disappear. The sandstone is fragile. The wind through the mountains, the pounding of feet, the universe'southward bent toward disintegration—all conspire to grind it abroad. My trip here was to encounter the place and take a measure of its evanescent beauty, and to watch Virtual Wonders, a company devoted to sharing and documenting the world's natural and cultural wonders, apply all fashion of modern technology to create a virtual model of the site so precise that it will, in effect, freeze Petra in time.

* * *

I arrived in Petra but as the summer sun cranked up from roast to broil; the sky was a bowl of blue and the midday air was pipage hot. The paths inside the Petra Archaeological Park were clogged. Horse-fatigued buggies clattered by at a bone-joggling speed. Packs of visitors inched along, brandishing maps and sunscreen. In a spot of shade, guides dressed every bit Nabateans kneeled to conduct their midday prayers.

At its summit, ii,000 years ago, Petra was home to as many as xxx,000 people, full of temples, theaters, gardens, tombs, villas, Roman baths, and the camel caravans and marketplace bustle befitting the center of an ancient crossroads between due east and west. Later on the Roman Empire annexed the metropolis in the early second century A.D., it continued to thrive until an earthquake rattled information technology hard in A.D. 363. Then trade routes shifted, and by the middle of the seventh century what remained of Petra was largely deserted. No one lived in it anymore except for a small tribe of Bedouins, who took upward residence in some of the caves and, in more than recent centuries, whiled away their spare time shooting bullets into the buildings in hopes of cracking open up the vaults of gold rumored to exist inside.

In its period of abandonment, the city could hands have been lost forever to all just the tribes who lived nearby. But in 1812, a Swiss explorer named Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, intrigued by stories he'd heard nearly a lost metropolis, dressed equally an Arab sheikh to beguile his Bedouin guide into leading him to it. His reports of Petra's remarkable sites and its fanciful caves began drawing oglers and adventurers, and they have continued coming always since.

Ii hundred years afterwards, I mounted a donkey named Shakira and rode the dusty paths of the city to ogle some of those sites myself. This happened to exist the middle of the week in the middle of Ramadan. My guide, Ahmed, explained to me that he had gotten permission to accept his blood force per unit area medication despite the Ramadan fast, and he gobbled a scattering of pills every bit our donkeys scrambled upwardly rock-hewn steps.

Ahmed is a broad man with green eyes, a grizzled bristles, a smoker'due south cough, and an air of bemused weariness. He told me that he was Bedouin, and his family unit had been in Petra "since time began." He was born in one of Petra's caves, where his family had been living for generations. They would still be living there, he said, except that in 1985, Petra was listed equally a Unesco Globe Heritage site, a designation that discourages ongoing habitation. Almost all the Bedouin families living in Petra were resettled—sometimes against their wishes—in housing built outside the boundaries of the new Petra Archaeological Park. I asked Ahmed if he preferred his family's cave or his house in the new village. His house has electricity and running h2o and Wi-Fi. "I liked the cavern," he said. He fumbled for his phone, which was chirping. We rode on, the donkeys' difficult hooves tapping a rhythmic beat on the stone trail.

Petra sprawls and snakes through the mountains, with most of its pregnant features collected in a flat valley. Regal tombs line i side of the valley; religious sites line the other. A wide, paved, colonnaded street was once Petra'due south main thoroughfare; nearby are the ruins of a grand public fountain or "nymphaeum," and those of several temples, the largest of which was probably dedicated to the Nabatean sun god Dushara. Another, the in one case complimentary-continuing Cracking Temple—which probably served as a financial and civic center in addition to a religious one—includes a 600-seat auditorium and a complex arrangement of subterranean aqueducts. On a pocket-size rise overlooking the Bully Temple sits a Byzantine church with beautiful intact mosaic floors decorated with prancing, pastel animals including birds, lions, fish and bears.

The grander buildings—that is, the grander caves—are as high and spacious as ballrooms, and the hills are pocked with smaller caves as well, their ceilings blackened by the soot left from decades of Bedouin campfires. Some of the caves are truly imposing, like the Urn Tomb, with its classical facade carved into the cliff on top of a base of stone-built arches, and an eroding statue of a homo (perhaps the male monarch) wearing a toga. Others are easy to miss, such equally the cave known as the Triclinium, which has no facade at all but possesses the just intricately carved interior at Petra, with stone benches and walls lined with fluted half-columns. Continuing inside the valley it is like shooting fish in a barrel to run into why Petra thrived. The mountains comprise it, looming like sentries in every direction, but the valley itself is wide and bright.

And so much of Petra feels similar a sly surprise that I became convinced the Nabateans must have had a humour to take built the city the way they did. They were gifted people in many means. They had a knack for concern, and cornered the market place in frankincense and myrrh. They had real estate savvy, establishing their metropolis at the meeting point of several routes on which caravans shipped spices, ivory, precious metals, silk and other goods from China, India and the Persian Gulf to the ports of the Mediterranean. They had a talent for melding the dust and dirt around them into a hard, russet clay from which they made perfume bottles and tiles and bowls. They were adept artisans. And while information technology isn't recorded in historical texts, they clearly appreciated the hallmarks of architectural showmanship—a good sense of timing, a flair for theatrical siting.

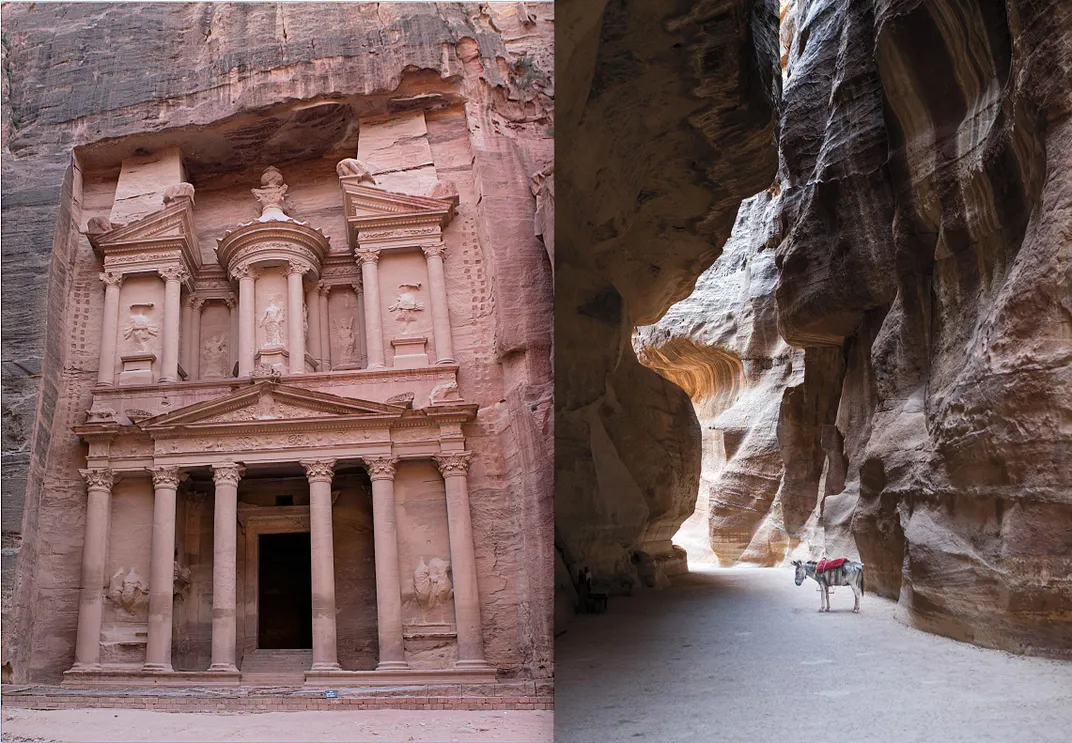

The most convincing testify of this begins with the Siq, the main entrance to the metropolis, a natural ravine that splits the towering rocks for almost a mile. Information technology'due south a compressed, bars space; its rock walls lean this way and that. Once y'all inch your mode through information technology, you are spilled out onto a sandy apron and confronted with the nigh dramatic construction in Petra—Al Khazneh, or the Treasury, a cave more a hundred feet loftier, its facade a fantastical mash-upwardly of a Greco-Roman doorway, an Egyptian "broken" pediment and 2 levels of columns and statues etched into the sheer face of the mountain.

The Treasury wasn't actually a treasury at all—information technology gets its name from the riches said to take been stored in the great urn atop the circular building at the facade's center. The statues adorning the colonnaded niches suggest it may have been a temple, just most scholars call up it was a tomb housing the remains of an important early on king. (A favorite candidate is the first century B.C. Aretas Three, who used the word Philhellenos on his coins—"friend of the Greeks"—which might explain the building's Hellenistic flair.) Inside the cave there are just three bare chambers, today empty of whatever remains once rested there.

Possibly the Nabateans placed this grand building here because the Siq served as a buffer to marauders, much like a wall or a moat. Just I can't aid simply think that they knew that forcing visitors to approach the Treasury via a long, boring walk through the Siq would make a perfect lead-up to a great reveal, designed to please and astonish. The gradual approach also leaves the world with a timeless pun, considering coming upon the Treasury this fashion makes you feel as if yous've found a treasure at the end of a hugger-mugger grotto.

Life in the Big Urban center

Petra was a nexus of commerce and cultural exchange

When the Nabateans established their capital at Petra they ensured that information technology was well continued to booming merchandise routes: the Silk Road to the north, Mediterranean ports to the westward, Egypt and southern Arabia to the due south. With trading partners across the ancient globe, the seat of Nabatean ability was "the very definition of a cosmopolitan trade center," writes the classicist Wojciech Machowski.

* * *

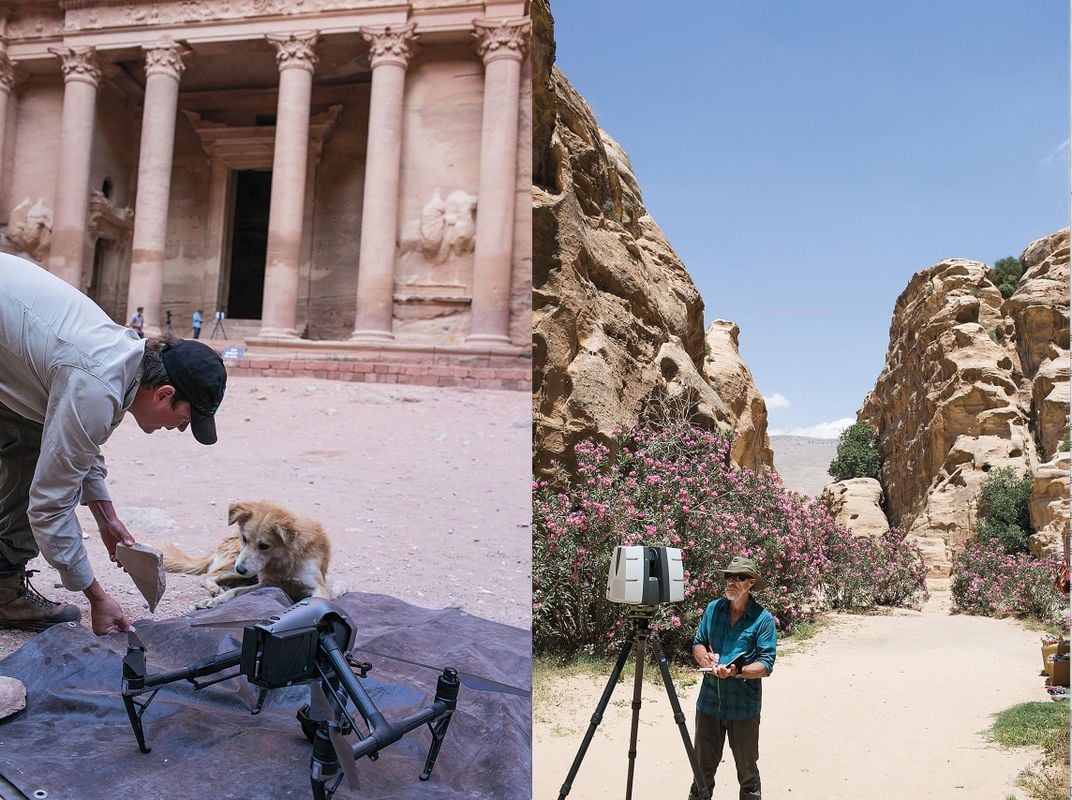

As Ahmed and I rode along, I could just brand out in the distance the team from Virtual Wonders, who had spent the twenty-four hours flying a drone over the Great Temple, shooting high-resolution images of it from above. The company was formed in 2018 by three friends with complementary talents. Mark Bauman, a longtime journalist and former executive at Smithsonian Enterprises and National Geographic, knew the people in accuse of historical locations like Petra and how to work with local authorities. Corey Jaskolski, a one-time high school dropout/computer whisperer (he somewhen earned a graduate degree from MIT in electrical engineering), who has patented systems for impossible-seeming robotic cameras and 3-D scanning for employ underwater, on country and from the air, would manage the technological challenges of image capture and digital modeling. Kenny Broad, an environmental anthropologist at the Academy of Miami, is a world-class cave diver and explorer for whom scrambling around a place like Petra was a slice of cake; he would serve as chief exploration officer. The three of them shared a passion for nature and archæology and a concern with how to preserve important sites.

While outfits such as the Getty Research Institute and the nonprofit CyArk accept been capturing iii-D images of historical sites for some time, Virtual Wonders proposed a new arroyo. They would create infinitesimally detailed 3-D models. For Petra, for case, they would capture the equivalent of 250,000 ultra-high-resolution images, which will be reckoner-rendered into a virtual model of the city and its breathtaking structures that can be viewed—even walked through and interacted with—using a virtual-reality headset, gaming panel or other high-tech "projected environments." Virtual Wonders will share these renderings with regime and other scholarly and educational partners (in this case, the Petra National Trust). Detailed modeling of this kind is at the leading border of archaeological best practices, and according to Jordan's Princess Dana Firas, the head of the Petra National Trust, the data will aid identify and measure the site'due south deterioration and assist in developing plans for preservation and managing visitors. "It'due south a long-term investment," Firas told me.

By the time I arrived in Petra, the Virtual Wonders team had scanned and imaged more than half of Petra and its significant buildings using an assortment of high-tech methods. A DJI Inspire drone—for which a military escort is required, because drones are illegal in Hashemite kingdom of jordan—uses a high-resolution camera to collect aeriform views, shot in overlapping "stripes" and so every inch is recorded. Exact measurements are done by photogrammetry, with powerful lenses on 35-millimeter cameras, and Lidar, which stands for Light Detection and Ranging, a revolving laser machinery that records infinitesimal calculations at the charge per unit of a million measurements per second. When combined and rendered past computers those measurements form a detailed "texture map" of an object's surface. All of this data will be poured into computers, which volition need near eight months to render a virtual model.

None of this is inexpensive. In Petra, the Virtual Wonders team hiked around with well-nigh a half-million dollars' worth of gear. Co-ordinate to Bauman, the company'south hope is that the cost of the projects will exist recouped, and exceeded, by licensing the data to film companies, game developers and the like, with a portion of the acquirement going dorsum to whoever oversees the site, in this instance the Petra National Trust. This isn't an idle hope. Petra is and so spectacular that it has been used as a location in films, most famously Indiana Jones and the Last Cause; countless music videos; and every bit a setting in at least ten video games including Spy Hunter, OutRun two and Lego Indiana Jones. If its approach succeeded, Virtual Wonders hoped to move on to similar projects around the world, and since I left Jordan the company has begun piece of work at Chichen Itza, the Mayan city in the Yucatán. It has also scored a clear success with an immersive virtual reality exhibit titled "Tomb of Christ: the Church of the Holy Sepulchre Feel," at the National Geographic Museum in Washington, D.C.

I left my donkey and crossed through the ruins of the flat valley to join the team on a ridge overlooking the Great Temple. "Nosotros're shooting stripes," Jaskolski chosen out as the problemslike drone rose and jetted across the open sky toward the temple. Jaskolski's wife, Ann, was monitoring the drone on an iPad. She reached out and adjusted the drone'due south landing pad, a gray safe mat, which was weighed down with a rock to keep the gusty breeze from toying with it. The drone made a burbling sizzle as information technology darted over the temple. Somewhere in the distance a donkey brayed. A generator coughed and so commenced its low grumbling. "We're killing it!" Jaskolski called to Bauman, sounding a little similar a teenager playing Fortnite. "I'm actually crushing the overlap!"

Bauman and I hiked along the ridge to some other building known every bit the Blue Chapel. A few crooked fingers of rebar stuck out of some of the rock—evidence that some impuissant restoration had been attempted. Only otherwise, the construction was untouched, another remnant of the urban center that Petra once had been, a humming capital, where lives were lived and lost; an empire etched in time, where the city's carapace is all that remains.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/7a/ec7abaa7-b7b5-4113-b048-d79204bdb0e2/oct018_b09_petra.jpg)

* * *

On the far side of the valley from the Treasury, across the plain, Petra's architects kept another groovy fox upward their sleeve: Advert Deir, or the Monastery. This ancient temple is idea to have been dedicated to a deified Nabatean rex named Obodas I, and possesses Petra's largest carved facade. Merely the path in that location gives you no glimpse of it at all. For twoscore minutes Ahmed and I clung on as our donkeys climbed up the steep path. I kept my eyes glued to the dorsum of Ahmed'due south head and so I wouldn't take to see the sheer drop-off forth the edge of the trail.

Equally we made yet another turn with no edifice in sight, I began to wonder if I had misunderstood our destination. Even when Ahmed stopped and announced that we had arrived, in that location was nothing to see. The oestrus was getting to me and I was impatient. I grumbled that I didn't see anything. "Over in that location," Ahmed said, gesturing around a ragged stone wall. When I turned the corner, I was met with the full-frontal view of an enormous facade with an array of columns and doorway-shaped niches, about 160 feet wide and well-nigh as tall, carved into a rocky outcropping. It was so startling and cute that I gasped out loud.

Like and so many of the monuments here, the Monastery's interior is deceptively simple: a unmarried rectangular room with a niche carved into the back wall, which probably one time held a rock Nabatean icon. The walls of the niche itself are carved with crosses, suggesting the temple became a church during the Byzantine era—hence the name. The Monastery is said to be the best instance of traditional Nabatean compages—simplified geometric forms, the urn atop a rounded edifice at the centre. Information technology is believed that the Monastery'south architect took inspiration from the Treasury merely pointedly stripped abroad most of its Greco-Roman flourishes. In that location are no statues in the spaces cut between the columns, and overall information technology's rougher, simpler. Only out here, all alone, in forepart of a wide rock courtyard where Nabateans and travelers from across the aboriginal world came to worship or feast, the sight of the Monastery is profound.

I stared at Ad Deir for what felt like an eternity, marveling not but at the building merely the way information technology had provided the exquisite pleasure of delayed gratification. When I returned to Ahmed, he was on the phone with his ii-twelvemonth-onetime daughter, who was begging to get a new teddy comport on their upcoming trip to town. Ahmed has five other children. His oldest son, Khaleel, also works equally a guide in the park. Khaleel had taken me earlier in the day to a ledge in a higher place the Treasury, a view even more vertiginous than the trail to Ad Deir. I needed several minutes before I could inch to the edge and appreciate the view. When I steadied my nerves and was able to peek out through squeezed eyes, I could grasp the monumentality of the Treasury—how it loomed, emerging out of the mountainside like an apparition, a building that wasn't a edifice, a place that was there but non there.

What volition it mean to create a perfect model of a place like Petra—1 that you might be able to visit sitting in your living room? Will it seem less urgent to see Petra in person if you tin can stick on a pair of virtual reality goggles and brand your mode through the Siq, gawk at the Treasury, hike up to the Monastery, and audit ruins that are thousands of years old? Or will having access to an nearly-real version of Petra make information technology easier for more people to learn about it, and that, in turn, will brand more people care virtually it, even if they never walk over its red rocks or slide their way through the Siq? The preservation aspect of projects like Virtual Wonders' is undeniably valuable; it saves, for posterity, precise images of the world'southward great sites, and will allow people who won't ever have the opportunity to travel this far to see the identify and experience information technology nigh as it is.

But visiting a identify—breathing in its ancient dust, against it in real time, meeting its residents, elbowing its tourists, sweating every bit y'all clamber up its hills, even seeing how time has punished information technology—will always exist unlike, more than magical, more challenging. Technology makes information technology easier to see the earth about as it is, simply sometimes the harder parts are what brand travel memorable. The long climb to Advertising Deir, with its scary path and surprising reveal, is what I will remember, long later the specific details of the building'south advent have faded from my memory. The manner Petra is laid out ways you lot work for every gorgeous vision, which is exactly what I imagine the Nabateans had in mind.

* * *

As soon every bit I left Petra, I constitute myself staring at the pictures I had taken and finding it hard to believe I had been in that location; the images, out of context, were and then fantastical that they seemed surreal, a dream of a red stone city dug into the mountainside, so perfectly camouflaged that as soon as you drive the steep road out of the park, information technology seems to disappear, every bit if it were never in that location.

In Amman, where signs advertised this fall'south Dead Sea Fashion Calendar week ("Bloggers and Influencers Welcome!"), my driver pulled up to the front door of my hotel and I stepped out, passing a sign directing Fashion Week attendees to the ballroom. The hotel had only opened for business—it was a sleeky, glassy building that advertised itself as being in the heart of the new, modern Amman. Just ancient Jordan was here besides. The entry was puzzlingly nighttime and small, with a narrow opening that led to a long hallway with walls that were akimbo, leaning in at some points and flaring out in others, with precipitous angles jutting out. I inched along, dragging my suitcase and banging a corner here and at that place. Finally, the dark hall opened wide onto a large, bright anteroom, so unexpected that I stopped cold, blinking until my eyes adapted to the calorie-free. The young homo at the reception desk nodded at me and asked if I liked the archway. "It's something special," he said. "We telephone call it the Siq."

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/petra-jordan-drone-3d-scan-digital-modeling-180970310/

Belum ada Komentar untuk "People Staring at a Great Ancient City Clip Art"

Posting Komentar